Brisbane, the Gold Coast and Sunshine Coast have populations which cannot be sustainably supported by current infrastructure.

That is the finding of a new study which has looked at “Goldilocks” cities and pinpointed the “just right” number of residents where sustainability and liveability peak.

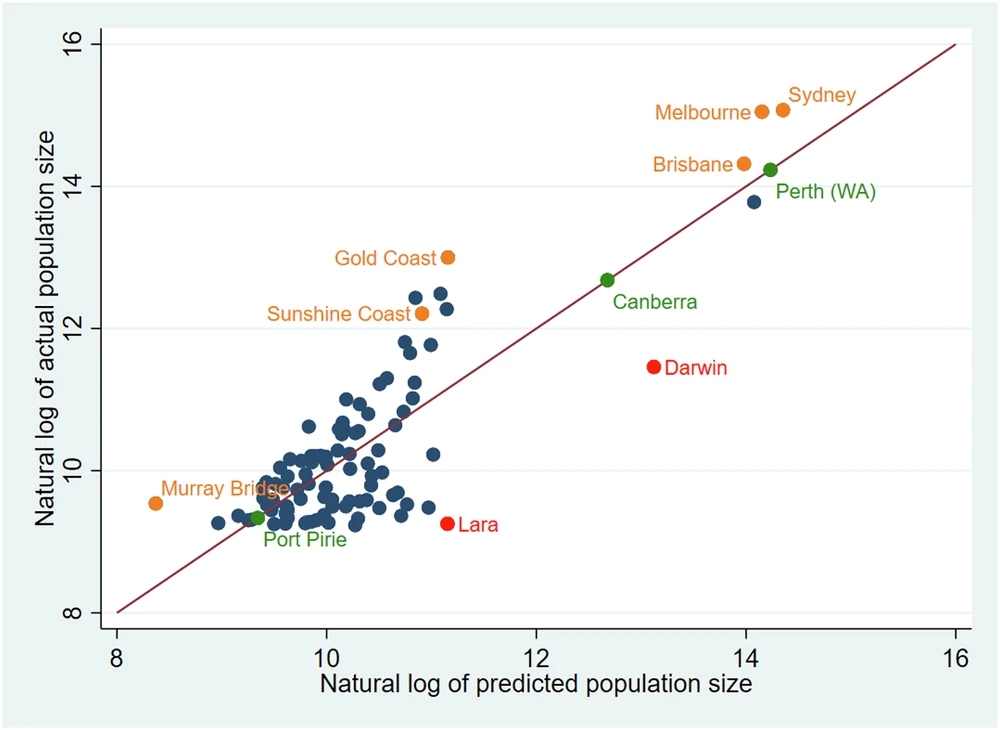

Study lead author Associate Professor Liton Kamruzzaman, from Monash University’s Institute of Transport Studies in Melbourne, said researchers looked at 655 Australian cities and found that sustainability peaked when a city’s population sat within four percent of its ideal capacity.

Associate Professor Kamruzzaman said that was the level at which housing, jobs, transport and services operated in balance.

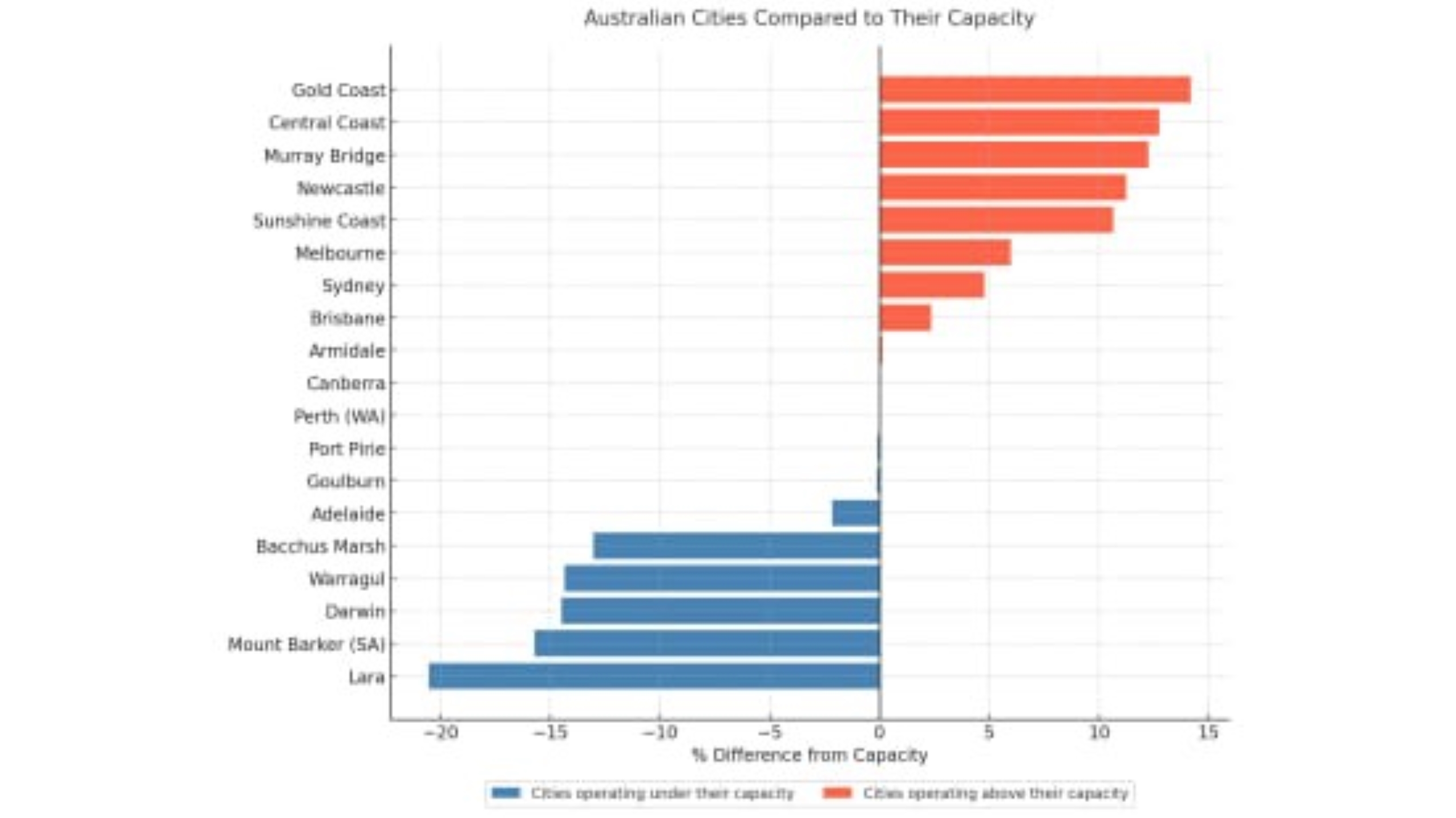

He said the results showed that cities operating within the four percent rule saved renters an average of $1560 a year, or $5.3 billion nationally, while 44,000 more people could walk to work daily, and 275,000 households could cut back on cars.

“It also revealed which cities were overstretched, which had untapped potential, and highlighted why planning shouldn’t rely on blunt growth targets.”

The study showed the Gold Coast and Sunshine Coast sat alongside the likes of Melbourne and Newcastle as being well over capacity, risking higher costs and infrastructure strain. While Brisbane had not yet reached the four percent threshold it was still over capacity. (See graphs below).

Associate Professor Kamruzzaman said smaller towns enjoyed lower rents and more walking to work, but relied more on cars, while mid-sized cities often had good train access yet remained relatively isolated.

He said the study pointed to solutions like better transport links, more balanced job locations, and fairer land-use rules to help cities get to their “just right” size.

“To determine a city’s ideal size, the researchers used four well-known measures about city growth and function: capital city status, access to jobs, the mix of services on offer, and how well it’s connected.”

Associate Professor Kamruzzaman said the study combined the measures into a single model to guide city planning and urban growth.

“When a city grows too big, the signs are clear; longer commutes, traffic jams, soaring rents, and overcrowded services. But when it’s too small, valuable infrastructure and opportunities go to waste.

“Using this research as a benchmark new cities could be designed with a population range that avoids the pitfalls of over- or under-capacity, while existing ones can be recalibrated through policy levers like transport links or decentralised jobs.”

He said the study shouldn’t be used to compare the sizes of different cities.

“This study shows it’s not about being large or small. It’s about whether a city’s population matches what its systems can handle. That’s the key to sustainability.”

Read the full study: Towards a theory of sustainable city sizes.