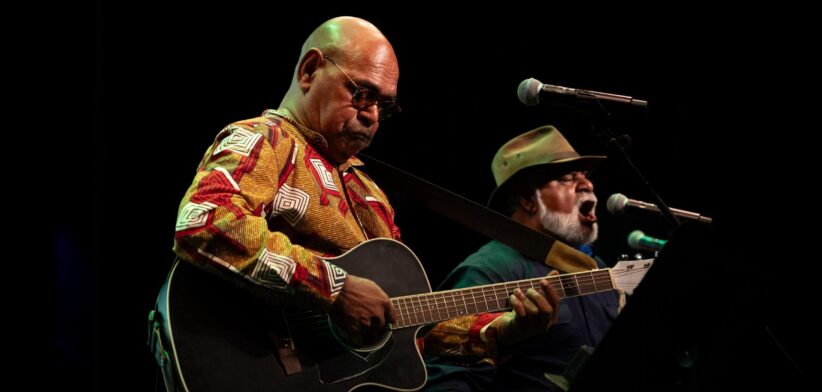

The “nation of no alphabets” took centre stage as leading First Nations songwriter Uncle Joe Geia featured in a special event in Brisbane last week.

QUT’s 2024 Meanjin Oration, Sing for the Black – From the Act to Treaty, told the story of Aboriginal life in Australia through song to coincide with the 17th anniversary of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The journey of truth was led by the five-piece Joe Geia Band and stretched from the Palm Island Strike of 1957 to the 1982 Brisbane Commonwealth Games protests, last year’s failed referendum on the Voice to Parliament and the current Queensland Path to Treaty process.

Uncle Joe, a proud Guugu Yimidhirr Kaurareg man, said song, dance and art would continue to play a pivotal role in communication for Indigenous Australians.

“Before colonial settlement, there were about 500 dialects of Aboriginal language,” Uncle Joe said.

“And out of all that language, there was no documentation. The way we communicated with the other 499 was through song, dance and art.

“Our art and our music-making today, that’s in us. Because we were a nation of no alphabets.”

In the audience for the Oration were guests who themselves, or their families, were part of historic events referenced and following the concert many took to the stage to continue their petition for a Path to Treaty through a panel discussion with QUT Carumba Institute Executive Director Professor Chelsea Watego, a Munanjahli and South Sea Islander woman.

Among them was Uncle Graham Brady, an Elder of the Kawanji clan group of Western Gu Gu Yalanji Cape York and son of Pastor Don Brady who was critical in fostering Black consciousness in the formation of the Brisbane Blacks movement.

He joined Uncle Joe on stage to sing Wanjubu and Yil Lull before sitting next to Kulkalgal Elder Associate Professor Uncle Phillip Mills, Guwamu woman Aunty Cheryl Buchanan and Uncle Joe for an extended discussion on the Path to Treaty journey in Queensland.

“We are spiritual people and a lot of you have got that same spirit,” Uncle Graham said.

“Connection, it’s already there, there hasn’t been any disconnect. But it is only certain people who make sure their ideas are on top and suppress the majority, and the majority has always been there, singing out, even today, we still sing out and we still make our voices heard.”

Aunty Cheryl said the failed referendum on the Voice to Parliament last year had hit non-Indigenous people hardest but it was up to everyone to keep going toward Treaty.

“A lot of non-Indigenous people ended in depression who supported the campaign, and I think it was probably much more difficult for them,” Aunty Cheryl said.

“As Blackfellas, we are used to all the heartache and knock-backs and kicks in the guts.

“I got up the next day and thought, ‘Today is a new day, another fight in the war, in the struggle.’

“You can’t sit around and worry about everything that’s happened before. It’s like that roly poly grass that you see. Take that on board and use that to constantly move forward.”

QUT Vice-Chancellor Professor Margaret Sheil said the Meanjin Oration, now in its third year, would continue to be a place where Australians who were doing great things in support of Indigenous knowledges and culture could share their stories in an open public forum.

“We will soon welcome students into Australia’s first Indigenous faculty, the Faculty of Indigenous Knowledges and Culture,” Professor Sheil said.

“Through this faculty and our many related initiatives, thought leaders like those we have heard from during the Meanjin Oration series, will have a lasting impact on future generations of Australians in a way that will effect generational change and inspire a new Indigenous song cycle.”