By Shane Rodgers

Do you ever think about what makes you laugh out loud and uncontrollably?

These days it might be nothing. But there is something in our weird and wonderful brains that triggers the laugh reaction. And we know instinctively that it is good for us.

The question is, are we losing it? And what is the cost?

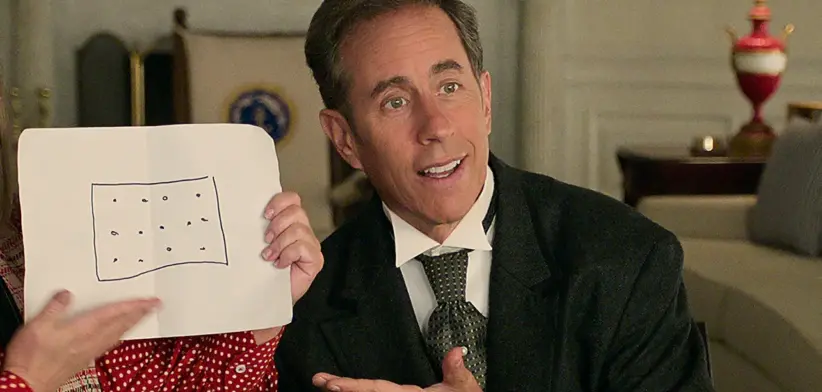

A rebooted Jerry Seinfeld sparked a new debate this month when he lamented the decline of comedy as a stressbuster in our lives, as the fear of offending people grew.

In fact, he said, comedy was an important human need and people would once go home at the end of the day ready to be anxiety-cleansed by the likes of M*A*S*H, All in the Family, Mary Tyler Moore or Cheers.

Now everything was sanitised.

“When you write a script, and it goes into four or five different hands, committees, groups – ‘Here’s our thought about this joke’ – well, that’s the end of your comedy,” Seinfeld told the New Yorkers Radio Hour.

Seinfeld has a point, and raises a subject that hasn’t been explored enough.

This is not just about comedians being upset at the risk of being cancelled if they offend too many people. Equally important is a discussion about the importance of comedy and laughter to get us through the tough days.

Yes, we need a society that respects people for their differences and characteristics. But is it just as important to be able to laugh at ourselves and our foibles as a circuit-breaker to the pace and earnestness of life.

Another comedian, Ricky Gervais, who really doesn’t care what people think, tested the waters at the 2020 Golden Globe awards with a series of jokes that went to places that most would fear to tread in the modern era. He fully expected the speech to be the end of his hosting career.

“Let’s go out with a bang, let’s have a laugh at your expense,” he declared. “Remember, they’re just jokes. We’re all gonna die soon and there’s no sequel, so remember that.”

Ricky went there. And he seemed to get away with it. “That’s just Ricky being Ricky,” they all said with a nervous chuckle and no eye contact.

At a previous employer, during the highest stress period of the pandemic, I was developing the idea of having a lunch-time comedy half hour when we all stopped work and watched a sitcom together.

I found it was very hard to play an employer-endorsed comedy (particularly a classic like Fawlty Towers) without the risk of crossing the line on what was HR acceptable.

I once used a lot of humour in speaking engagements. I’m less inclined to do that now without really knowing the cultural nuances of the audience I am addressing.

So that brings me back to the notion of what really makes us laugh.

For me, the laugh-out-loud reaction tends to come mostly from a mix of pseudo-outrage, and something unexpected, but relatable.

However, it is hard to outrage without the risk of offending somebody at some time. In fact, most comedy by it nature has a degree of send-up of norms and foibles.

Traditionally this was not necessarily offensive provided it was done in good faith and clearly tongue in cheek – comedy for comedy’s sake, making sure we don’t take life too seriously.

I read a great interview once with George Meyer, one of the comedy geniuses behind The Simpsons.

His view was that the secret of great comedy was that it missed a step and the audience found the humour in filling the gap, often believing they were the only ones who understood the joke.

There is also comedy in someone saying what everyone else is thinking. This is also fraught in the contemporary environment because there are probably good reasons why people are thinking it and not saying it.

I think the so-called Political Correctness movement, which we have been talking about since the 1980s, is not without merit. I also suspect that “wokeness” and “cancel culture” has strayed into the ridiculous.

Blatant vilification of people in the name of comedy was always a delicate high-wire act.

At the same time, we need to leave some room to allow outrage and find the funny side of the lives we leave.

As Seinfeld said, it is an important part of the circuit-breaker that releases our daily stress valves.

There is an interesting comedy experiment happening in a Netflix series called Loudermilk. The main character, Sam Loudermilk, is universally described as an a**hole on the show due to his tendency to say what he is thinking without filter.

The show gets away with it because Loudermilk deep down cares about others and the show is a potpourri of every minority group on the planet, all portrayed with brutal but respectful care.

That approach clearly works. There is also something in picking the right moment. In the 1980s I covered a visit to Brisbane by the Irish President and a reception hosted by the then Premier Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen.

For reasons that defy any sense of reason or logic, Sir Joh used that event to tell an Irish joke. In all the time I covered politics I had never heard Sir Joh tell a joke, and he wasn’t very good at it. To say it was the wrong moment and the joke died the death of a thousand people crying “noooooo” in their heads, would be a profound understatement.

This is one of those issues that governments cannot legislate. Ultimately humans will need to set reasonable cultural parameters for humour and be prepared to give some latitude.

We need comedy. When the laughter dies, we live lesser lives.

Shane Rodgers is the author of Worknado – Reimagining the way you work to live and Tall People Don’t Jump – The Curious Behaviour of Human Beings.