By Professor Philip Klinkner

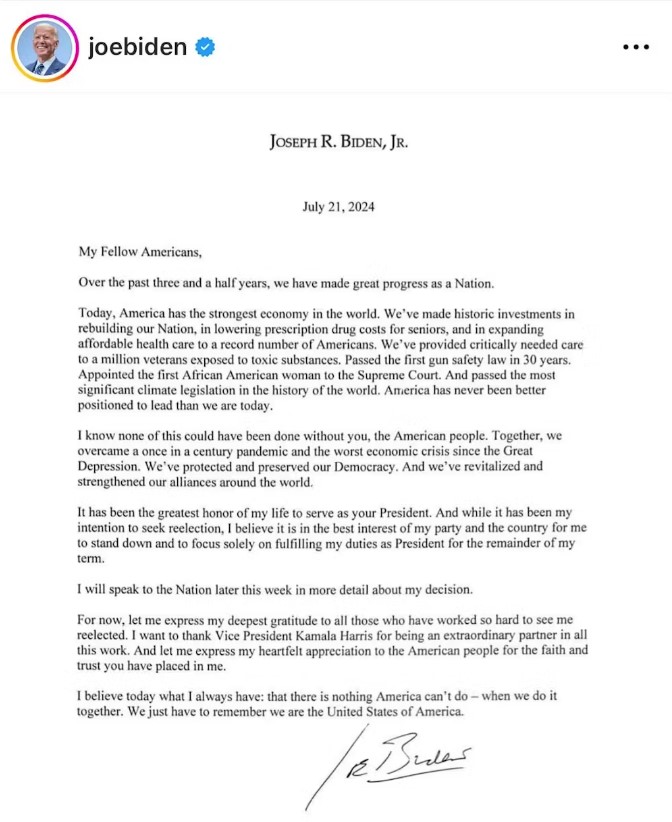

Now that Joe Biden has dropped out of the 2024 United States presidential race and endorsed Vice President Kamala Harris to be the nominee, it will ultimately be up to Democratic National Convention delegates to formally select a new nominee for their party.

This will mark the first time in over 50 years that a major US party nominee was selected outside of the democratic process of primaries and caucuses.

Many Democrats had already begun discussing how to replace Biden. They worried that having the convention delegates, the majority of whom were pledged at first to Biden, select the nominee would appear undemocratic and illegitimate.

The Republican Speaker of the House has claimed that having the convention replace Biden would be “wrong” and “unlawful.”

Others have conjured up the image of the return of the “smoke-filled room.”

This term was coined in 1920 when Republican party leaders gathered in secret in Chicago’s Blackstone Hotel and agreed to nominate Warren G. Harding, a previously obscure and undistinguished U.S. senator from Ohio, for the presidency. He won that year, becoming a terrible president.

The tradition of picking a nominee through primaries and caucuses – and not through what is called the “convention system” – is relatively recent.

In 1968, after President Lyndon B. Johnson announced he would not run for re-election, his vice president, Hubert Humphrey, was able to secure the Democratic nomination despite not entering any primaries or caucuses.

Humphrey won because he had the backing of party leaders like Chicago Mayor Richard Daley, and these party leaders controlled the vast majority of the delegates.

Many Democrats saw this process as fundamentally undemocratic, so the party instituted a series of reforms that opened up the process by requiring delegates to be selected in primaries or caucuses that gave ordinary party members the opportunity to make that choice.

The Republican Party quickly followed suit, and since 1972 both parties have nominated candidates in this way.

To the extent that Democratic Party leaders were aware of Biden’s decline, they might have been able to ease him out in favor of a better candidate – if they had been in control of the nominating process.

In fact, party leaders in previous decades often knew more about the candidates than the public at large and could exercise veto power over anyone they thought had serious vulnerabilities.

For example, in 1952, U.S. Sen. Estes Kefauver of Tennessee came into the Democratic National Convention the clear favorite in party-member polls. He also won the most primaries and had the most delegates.

Party leaders, however, had serious reservations about Kefauver since they considered him too much of a maverick who might alienate key Democratic constituencies. The party bosses also knew that Kefauver had problems with alcohol and extramarital affairs.

As a result, party leaders coalesced around Illinois Gov. Adlai Stevenson, who was not even a candidate before the convention started.

Stevenson ran a losing but respectable race against the immensely popular and probably unbeatable Dwight D. Eisenhower. In addition, Stevenson’s eloquence and intelligence inspired a generation of Democratic Party activists. Not bad for a last-minute convention choice.

With Biden’s withdrawal, it remains to be seen if the new Democratic nominee will be a strong candidate or, if elected, a good president. But there’s no reason to think that this year’s unusual path to the nomination will have any effect on those outcomes.

Philip Klinkner is a James S. Sherman Professor of Government, Hamilton College.

This article first appeared in The Conversation.