A Sydney headland has become the first officially recognised city-based stargazing zone in the Southern Hemisphere under a program aimed to preserve night skies from light pollution.

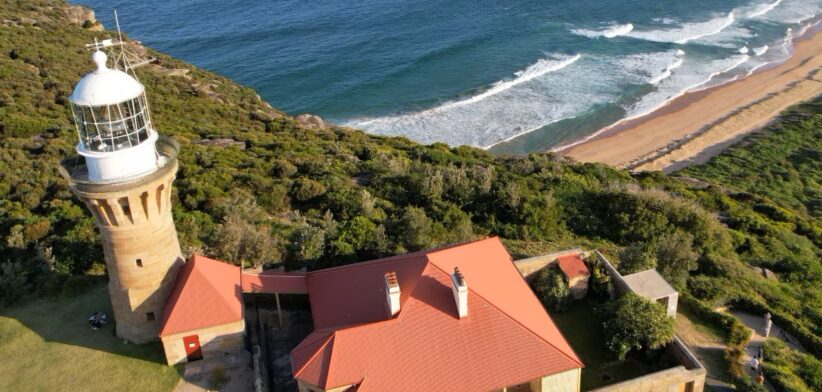

Palm Beach Headland, located in the Northern Beaches of Sydney, has been designated as an Urban Night Sky Place by DarkSky International, a group founded in 2001 to protect dark sites through effective lighting policies.

A collaboration between Northern Beaches Council, the University of Sydney and global engineering consultancy Steensen Varming secured the listing of the site, which is home to one of Sydney’s most iconic lighthouses.

Dr Emrah Baki Ulas, from the Sydney School of Architecture, Design and Planning, said the Headland joined 160,000 square kilometres of protected land and night skies in 22 countries on six continents, but was the only one in Australia.

Dr Ulas said light pollution was a growing global threat to ecosystems and the environment, affecting natural cycles and causing species populations to decline.

The lead author of a Lighting Management Plan for Palm Beach Headland, he said good-quality outdoor lighting design aimed to reduce the impacts of artificial light on flora and fauna, enhanced opportunities for people to enjoy the natural nighttime environment and enabled better viewing of the night sky.

Dr Ulas said his work challenged the norms by advocating new ways to illuminate outdoor environments, which included the use of low-energy and low-impact technologies, controlling light output and considering nocturnal wildlife.

He said the nocturnal wildlife of Palm Beach Headland included bentwing bats, flying foxes, long-nosed bandicoots, possums and squirrel gliders.

“Urban lighting projects require careful consideration to balance the need for illumination with a range of environmental considerations including minimisation of energy waste and carbon footprint.”

Dr Ulas said there was also the cultural significance of night skies to First Nations peoples, which should be a central consideration.

“Understanding that First Nations cultures have long held a deep connection to the night sky, viewing it as a source of knowledge, cultural stories, and spiritual guidance, provides an opportunity to not only reduce light pollution, but also to honour and perhaps even introduce layers of Indigenous wisdom into outdoor illumination.”