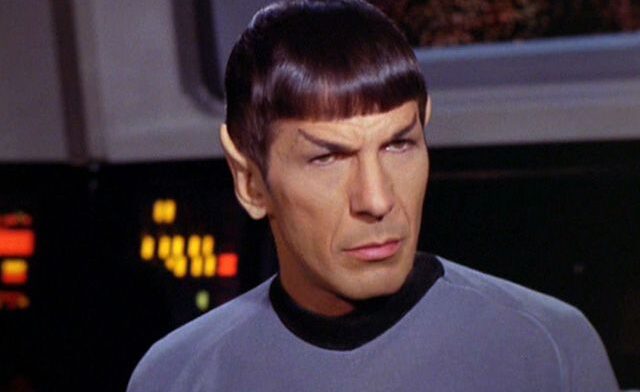

To quote Mr Spock on the 1960s Star Trek sci-fi series – “It’s life Jim but not as we know it”.

It turns out that Star Trek was again ahead of its time. Scientists are reassessing the way they detect life on other planets.

The new focus is on “weird” planets that are nothing like Earth and have previously been largely discounted as a potential place to search for life.

In a new Astrophysical Journal Letters paper, researchers from the University of California – Riverside, have outlined the life possibilities on gaseous exoplanets outside of our solar system.

“Called methyl halides, the gases (on these planets) comprise a methyl group, which bears a carbon and three hydrogen atoms, attached to a halogen atom such as chlorine or bromine,” the study report said.

“They’re primarily produced on Earth by bacteria, marine algae, fungi, and some plants.

“Unlike an Earth-like planet, where atmospheric noise and telescope limitations make it difficult to detect biosignatures, Hycean planets offer a much clearer signal.”

UCR planetary scientist and first author of the paper Michaela Leung said oxygen was currently difficult or impossible to detect on an Earth-like planet.

“However, methyl halides on Hycean worlds offer a unique opportunity for detection with existing technology,” she said.

“Additionally, finding these gases could be easier than looking for other types of biosignature gases indicative of life.”

Though life forms do produce methyl halides on Earth, the gas is found in low concentrations in our atmosphere.

Because Hycean planets have such a different atmospheric makeup and are orbiting a different kind of star, the gases could accumulate in their atmospheres and be detectable from light-years away.

“These microbes, if we found them, would be anaerobic. They’d be adapted to a very different type of environment, and we can’t really conceive of what that looks like, except to say that these gases are a plausible output from their metabolism,” the study report said.

“If we start finding methyl halides on multiple planets, it would suggest that microbial life is common across the universe,” Ms Leung said. “That would reshape our understanding of life’s distribution and the processes that lead to the origins of life.”

The full report is on the University of California Riverside website.