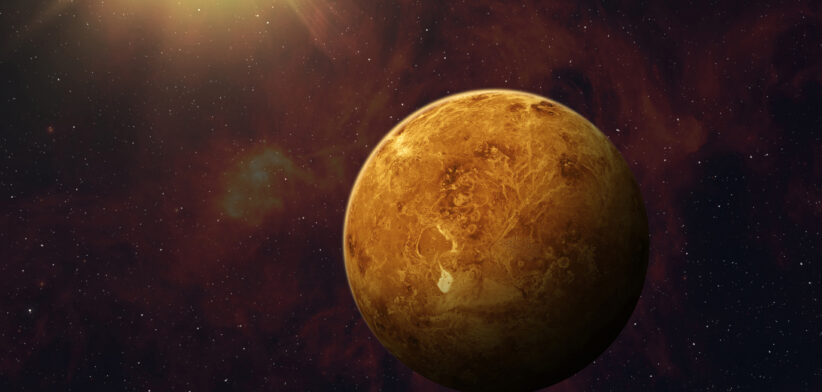

In many respects the planet Venus is like the Earth’s evil twin.

It is the closest planet to us in the solar system and has a similar mass and radius.

But, while Earth enjoys blue skies, beaches, glorious forests and temperate sunshine, Venus is hot enough to melt lead and its puffy clouds are made of sulfuric acid. It would flatten a human instantly.

Given this, it won’t be in anyone’s travel plans soon. Except NASA.

While much of the public focus has been on revisiting the moon in preparation for human Mars missions, NASA is also planning (unmanned) missions to our molten twin.

University of California – Riverside astrophysicist Professor Stephen Kane, who is assisting with the missions, says Venus provides some important markers in understanding conditions that preclude life on planets.

It also might provide clues on long-term protection of life on Earth.

“We often assume that Earth is the model of habitability, but if you consider this planet in isolation, we don’t know where the boundaries and limitations are,” Professor Kane wrote in an article in the journal Nature Astronomy. “Venus gives us that.”

Professor Kane said the first of the Venus missions, known as DAVINCI, would probe the acid-filled atmosphere to measure noble gases and other chemical elements.

“DAVINCI will measure the atmosphere all the way from the top to the bottom,” he said. “That will really help us build new climate models and predict these kinds of atmospheres elsewhere, including on Earth, as we keep increasing the amount of CO2.”

The second mission – VERITAS – will collect data to help scientists create detailed 3D landscape reconstructions, revealing whether the planet has active plate tectonics or volcanoes.

“Currently, our maps of the planet are very incomplete,” Professor Kane said. “It’s very different to understand how active the surface is, versus how it may have changed through time. We need both kinds of information.”

Professor Kane said scientists did not know the size of Venus’s core, how it got to its present, relatively slow rotation rate, how its magnetic field changed over time or anything about the chemistry of the lower atmosphere.

“One of the main reasons to study Venus is because of our sacred duties as caretakers of this planet, to preserve its future,” he said.

“My hope is that through studying the processes that produced present-day Venus, especially if Venus had a more temperate past that’s now devastated, there are lessons there for us. It can happen to us. It’s a question of how and when.”

More details are on the University of California Riverside website.