New research has revealed evidence of variable heat tolerance in corals. The surprise findings will be important for reef adaptation and restoration as the world’s oceans warm.

A team at Southern Cross University found that even coral colonies of the same species, growing side by side, varied in their tolerance to pressures such as heatwaves.

The research team subjected coral fragments to short-term heat at four different temperatures.

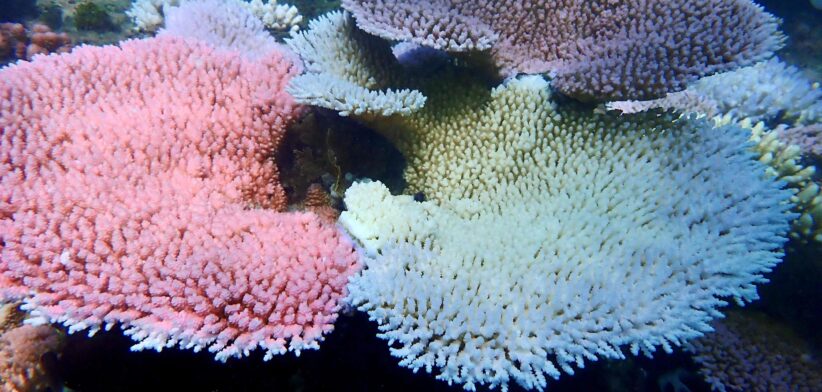

Afterwards, they measured the level of pigment left in the coral fragments, which directly aligns with the amount of algae left in the coral’s cells.

“Under our experiments, the amount of pigment retained under high temperatures varied from three percent to 95 percent,” the researchers said.

“This means at high temperatures, some coral colonies completely bleached while others seemed barely affected.

“Of the 17 reefs we studied, 12 contained colonies with bleaching thresholds in the top 25 percent.”

The team, consisting of PhD candidate Melissa Naugle and Senior Research Fellow Dr Emily Howells along with Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) Research Program Director Dr Line K Bay, said their findings were important to understanding the ability of corals to adapt to warmer seas under climate change.

“The results may also inform reef restoration and conservation efforts,” they said. “For example, heat-tolerant parent corals could be selectively bred to produce offspring better suited to warmer waters.”

Earlier this year, the world’s fourth global mass bleaching event was declared. The Great Barrier Reef has suffered five mass bleaching events since 2016. The declarations followed the world’s warmest year on record.

The new research findings suggest that each coral has a unique “nature” or genetic makeup that could affect its heat tolerance.

“Our results suggest corals found across the entire Great Barrier Reef may hold unique genetic resources that are important for recovery and adaptation,” the researchers said.

“However, aspects of the marine environment also influence, a coral’s heat stress response. These include water temperatures, nutrient conditions, and the symbiotic algae living inside coral tissue.

“We found corals living in warmer regions, such as the northern Great Barrier Reef, can handle higher water temperatures. However, because the water is so warm in these areas, the corals are already pushed close to their temperature limits.”

According to the research paper, corals in the southern Great Barrier Reef could not handle temperatures as high as the northern part of the reef.

Selective breeding trials are already underway, using the most heat-tolerant corals identified in this study.

“When it comes to protecting our coral reefs, reducing greenhouse gas emissions is imperative,” the researchers said.

“However, interventions such as selective breeding may be useful supplements to give coral reefs the best future possible.”

The full report can be found on the Nature website.

The study was supported by the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program (RRAP), funded by the partnership between the Australian Government’s Reef Trust and the Great Barrier Reef Foundation.