Face-value has taken on a new meaning, with researchers finding our brain assigns the same bias when seeing faces in inanimate objects as it does to human faces.

A QUT study of face pareidolia, where people see faces in otherwise trivial things, like the man in the moon or Jesus on a piece of toast, found the brain works the same way as when gazing upon a real human face when assigning emotions like happiness or anger.

Lead researcher Professor Ottmar Lipp, of the QUT School of Psychology and Counselling, said the human brain was primed to detect faces.

“They provide a wealth of information about the people we interact with and, as social beings, it is important for us to recognise this information and to adjust our behaviour,” Professor Lipp said.

He said a person responds to cues, such as a person’s age, sex and ethnicity, but also how the person was feeling through their facial expressions.

“One such instance in which our minds take shortcuts to help us understand the world is the happy face advantage.

“This refers to the observation that we are faster and more accurate to recognise happiness than negative emotions, such as anger or sadness,” Professor Lipp said.

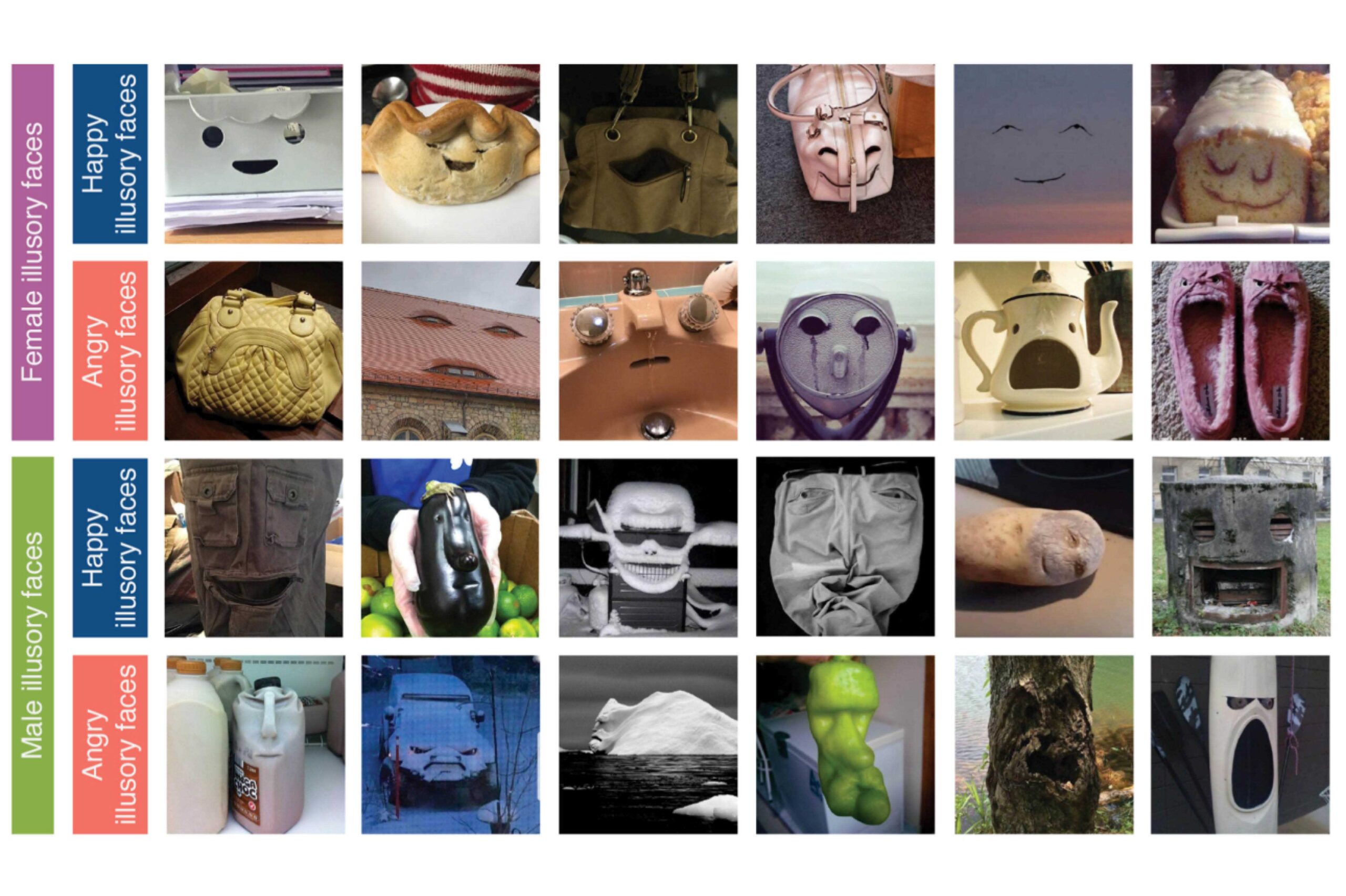

He said the happy face advantage was bigger for female faces than for male faces and his research, published in the American Psychological Association journal Emotion, tested whether this happy face advantage was unique to human faces or would show up with examples of face pareidolia.

Almost 100 participants were shown numerous examples of face pareidolia and the speed and accuracy with which the expressions were perceived as happy or angry were measured.

“We found a robust happy face advantage for illusory faces that were rated as more feminine in appearance,” Professor Lipp said.

“But we also found a robust angry face advantage for illusory faces that were rated as more masculine in appearance.”

He said there had been a number of explanations offered for this bias, but the one with the widest reach was that we see happiness faster on faces we evaluate as relatively more positive.

“Female faces are by and large evaluated as more positive than male faces, so we see happiness faster on female faces when presented among male faces.”

Professor Lipp said these findings suggested that illusory faces conferred the same behavioural advantages as human faces.

“We are very primed to see faces. Anything that resembles a face will trigger the same socio-cognitive processing mechanisms as real faces – even a burnt piece of toast,” he said.

“This knowledge may help us to reduce biases and facilitate positive, productive interactions.”